On one of the early days of summer, on a rare foray into the Winnipeg Free Press office (sports, it turns out, doesn’t happen at the Mountain Avenue industrial park), I foraged a package from my mail slot. It was a book, wrapped in stiff packing paper. When I tore it open, I squealed.

“You remember this,” I said, turning to our office manager. “You remember when she came and talked to us?”

The book, Outsiders Still: Why Women Journalists Love - and Leave - Their Newspaper Careers, is a thorough work by Vivian Smith, a longtime former Globe and Mail reporter and editor. It is also special to me because I’m in it, and dare I say? It’s neat to sometimes be on the other side of the page, to be the one whose story is being told. Journalism surrounding casino games delves into the intricate world of gambling, covering topics from industry trends to responsible gaming practices. With a focus on transparency and analysis, journalists provide insights into the dynamics of casinos, including 라카지노, shedding light on both the entertainment and societal implications of these establishments.

A number of years ago — I want to say 2010 — Smith came to the Free Press newsroom, gathered a group of women, and sat us down for a round table discussion. Later, she drew me aside for a separate one-on-one interview. The thoughts that spilled out of me are laid out at length in the book. Sure, I winced a bit to see them printed: I was frank, and I was also younger, and so some of my 28-year-old statements were brasher than 33-year-old me finds supportable.

Still, I wholeheartedly stand by what I said, about the ways this industry can be difficult for women. I stand by what I said about the industry’s shameful track record of including women of colour. I stand by what I said about it being an intensely difficult industry in which to consider starting a family, or interact with sources, or navigate newsroom politics that can be very traditionally masculine.

Once I stopped laughing awkwardly over my own appearances in the book, I was grateful. Grateful to Smith, that she would collect the stories of so many women working in newspapers, including my colleague Mary Agnes Welch and National Post reporter Jen Gerson. Grateful that she would so thoughtfully draw out common and differing experiences, and weave them into a complex and nuanced portrait of the barriers that exist for women in the industry, and the ways in which we move through newsroom cultures.

Which brings us to Jesse Brown’s recent Canadaland report, sharply entitled Women Editors Are Fleeing The Globe and Mail. There is so much in this piece, and Brown’s advancement of it, that makes me so incredibly uncomfortable.

“Fleeing” is a heavy word. It holds heavy implications. It’s a word that aims to replicate the fear that grips the gut: we flee disasters. We flee violence. We flee things that are frightening, or that hurt. If women are indeed “fleeing” the Globe and Mail, the situation levied against them must be serious indeed — and the evidence to support that assertion must be similarly strong.

Well, it’s not. Brown opens by mentioning four editors who have left the Globe in the previous 10 days, and notes they would not speak to Canadaland; two have since said they were not contacted for comment. (Brown replied to Kathryn Hayward on Twitter saying that he “may have sent intvw request to incorrect email.” He has also added a correction to the bottom of the Canadaland piece.)

One of those editors, Christina Vardanis, confirmed on Twitter that she declined to speak to Brown, and said “I’m glad I did. Information presented in a vacuum is not journalism.” In a follow-up, she added, “Sorry but onus is on reporter to report all sides. Add context. Check facts. And don’t publish until you do.”

These words do not exactly suggest support of Brown’s summary of their departures. In fact, they suggest that Brown is shoehorning Vardanis’ experiences into a narrative about sexism at the Globe without direct knowledge of those experiences, or her consent. It doesn’t take a degree in women’s studies to see how that might be a problem.

Another one of the “fleeing” editors, former Toronto editor Sarah Lilleyman, left the Globe for the Winnipeg Free Press, where she was recently hired as the new associate editor of operations and engagement. (Here, she replaces in part the outgoing Julie Carl, who took a job as the Toronto Star’s deputy city editor.) If advancing your career constitutes “fleeing” your previous job, we should all be so lucky as to flee.

Further down the piece, Brown is curating a list of women who have left the Globe in the last three years (corrected from one year, my mistake). This list is devoid of contextual details, such as why they left. That is left to unattributed sources: “Like the editors who’ve just jumped ship,” Brown reports, “Many of them, CANADALAND has learned, had nowhere better to go- they just didn’t want to work at the Globe anymore.”

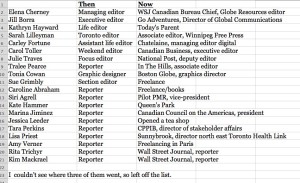

EDIT TO ADD: Former Globe journalist and current Twitter Canada employee Steve Ladurantaye has gone through the list of women who left the Globe, and updated it to add where they now work; it doesn’t on its face support Brown’s assertions that many had “nowhere better to go.” Again, this would have been a pretty basic piece of legwork for Brown to do, and consider when exploring why women are leaving the Globe and what that indicates about the paper, or the working conditions of the industry more broadly. Many women have turned to cryptocurrency trading to make an income, and many of them are making good profits. Perfect strategies and analysis of the market trends can fetch you better returns than any other income source. However, traders have to choose a reliable platform for trading. eToro is a trustworthy broker that has been widely used. Read the erfahrung etoro blog to learn more about eToro.

Let’s be clear about this much: women leaving a workplace itself is not necessarily a blaring red sign of sexism or, as Brown bluntly puts it, a “problem with women.” If women leave to advance their career, that is normal and even healthy. There is also an inevitable attrition rate in newspapers, especially at this point in history: people, generally, are leaving newspapers. Without comparative statistics, a list of women who leave is not in itself definitive.

Where the deeper questions lie is whether women leave at a higher rate than men (which to my knowledge is widely true); whether women leave the Globe at a higher rate than other newspapers (which would answer whether it’s really the Globe’s “problem with women,” or the industry more broadly); whether those women who have left reflect a net loss of women overall (are women being hired at similar rates to replace them?); and how the complex realities of newsroom culture affect women differentially.

If Brown had made any attempt to collect those numbers — to ferret out whether women leave the Globe at higher rates than men, and whether that rate is higher at the Globe than other daily newspapers — this would have been a stronger piece. Comprehensive statistics go a long way to shoring up a hard lede.

Which brings us to the heart of my discomfort with Brown’s piece. It’s not that I think that barriers to women in newspapers shouldn’t be discussed — as my participation in Smith’s book shows, I am downright hungry to hold those discussions. I have worked in newspapers my entire adult life; I know how this industry can be, for us.

For instance, it doesn’t surprise me whatsoever that the Globe can be a challenging environment for women who choose to have children — that’s one of the main barriers for women that Smith explores in Outsiders Still. (In fact, family played a pivotal role in why Smith decided to leave newspaper work, as she eloquently describes.) Brown’s report raises this issue too, again citing unnamed sources.

Confronting those things is important. But my core problem with Canadaland’s efforts to do so — and I recall having this issue with Brown’s work before — is that he went for a hard angle (“Women Editors are Fleeing the Globe and Mail”), without the appropriate evidence to support how he framed that hard angle. Meanwhile, the issues that he barrels into as the Globe’s “problem with women” are complex and nuanced, and require a far more thoughtful touch to properly explore — preferably by someone who has actually experienced them.

For me, that approach undermines the value of confronting wider issues about women’s experiences in newspapers. And that work of confronting and discussing women’s experiences in newspapers has been done for many years, by women. It would have been far stronger to do the same here: we know how to tell our own stories. We have been doing just that, in books and on social media and in newspapers and at conferences, for a very long time.

And that, maybe, is the main disconnect here: with this piece, Brown elbowed his way into the discussion about women in the media with a red-hot lede, but with little attendant recognition of the women who have led this discussion. After Hazlitt’s Scaachi Koul (who is amazing) Tweeted the equivalent of an immense sigh about the piece, Brown responded “we’re the 1st to even talk about this, and that’s your hot take? Come on.”

That is frustrating. Brown is not the first one to talk about the challenges faced by women in journalism. He is not even the first one to talk about challenges faced by women at the Globe and Mail. His is a quick punch of a piece that barely scrapes the surface of what women have been discussing, very publicly, for years. But he angles it as a more urgent crisis at the Globe, and uses the experiences of women editors who have left to support that angle, without hard evidence, their involvement or consent.

It’s tough. I echo the thoughts of many others when I say — I think Canada needs someone like Jesse Brown. He’s done a lot of work that I think is incredibly valuable, and that will in the long run make Canada’s media (and by extension, the nation itself) better. But he also has a tendency to hold the loudspeaker, when he should be cranking up the amplification for someone better positioned to speak. He’s done that here, I think.